A couple months ago I created felf, a library to parse ELF files into C++ structures, the reason for this was to have a way in C++ to work on ELF files using STL structures like vector, unordered maps and so on.

For this reason I wanna explore what was built and why, and show to you all the possibilities of this tiny yet nice library.

Executable files

What’s this ?

An executable file is designed to pack all information of a software into a single file that your OS will read, and do all the dirty work of mapping it’s code into memory and allocating resources that your CPU will use to execute.

These files are part of your life, now more than ever. You can find them in your SmartTV, Videogames, IoT devices and Unix systems

The ELF format is mainly used on Linux machines but it it’s not the only one that exists PE is mainly used in Windows, Mach-o is used in MacOS systems. Although this article and library will be focused on ELF and Linux machines, all the knowledge is the same that you need to work with PE and Mach-O files.

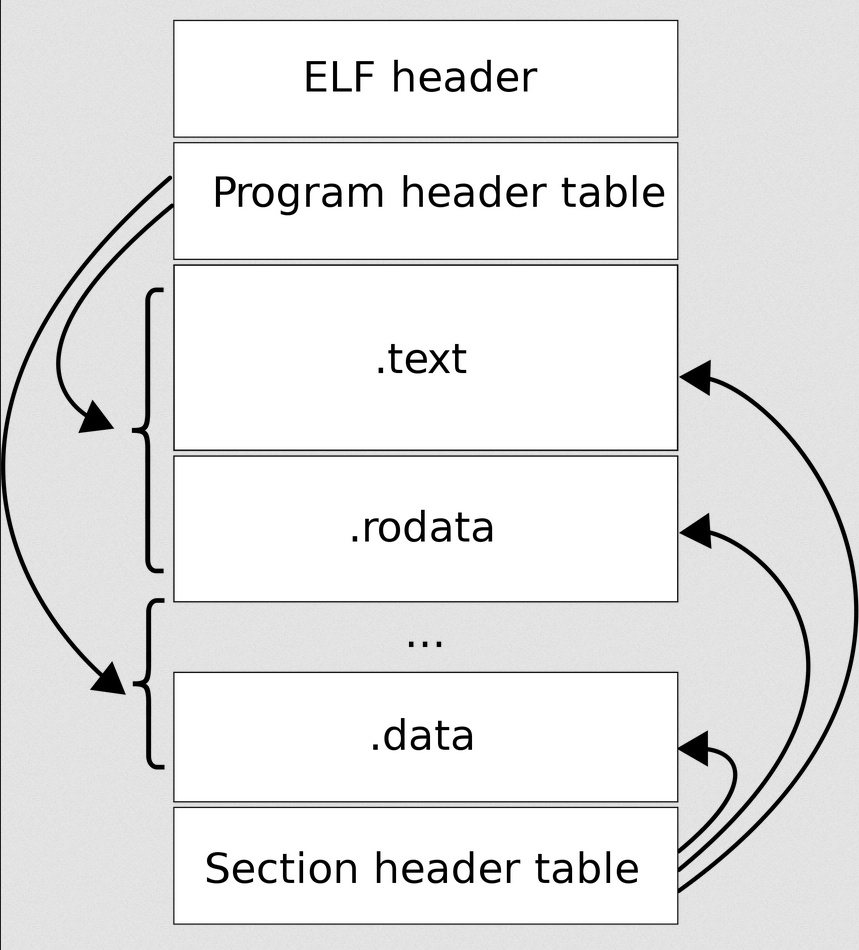

From disk to memory

Imagine ELF files as a pre-fabricated home, the way the file is on disk contains almost the same structures that will be mapped in memory and the steps the OS has to follow to do so in a correct way.

The structure is the follow:

Everything is pretty straight forward:

- A ELF header that holds the basic information of the file

- A program header table that describes each segment of code that will be mapped

- Sections that hold some data, like executable code, string table, symbol table and so on

- Section header which is a array like structure that holds information about a given section

ELF Internal structures

Each of these structures are defined in elf.h and if you run man elf you will get it’s full documentation. Let’s start by parsing in ELF header from disk (without loading anything in memory yet).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

#define EI_NIDENT 16

typedef struct {

unsigned char e_ident[EI_NIDENT];

uint16_t e_type;

uint16_t e_machine;

uint32_t e_version;

ElfN_Addr e_entry;

ElfN_Off e_phoff;

ElfN_Off e_shoff;

uint32_t e_flags;

uint16_t e_ehsize;

uint16_t e_phentsize;

uint16_t e_phnum;

uint16_t e_shentsize;

uint16_t e_shnum;

uint16_t e_shstrndx;

} ElfN_Ehdr;

This struct specifies a structure equivalent to the first bytes of the file. Notice that we have a N in the variable name that can be used with 32 or 64 bits depending the OS and the file itself, the ELF header size can be 52 bytes in 32-bit files and 64 bytes in 64-bits files, you can verify that by looking the structs sizes:

1

2

3

4

#include <elf.h>

...

printf("%d bytes\n", sizeof(Elf32_Ehdr)); // 52 bytes

printf("%d bytes\n", sizeof(Elf64_Ehdr)); // 64 bytes

Parsing the header from scratch

As my system currently is in 64 bits, I will first dump out the first 64 bytes of data from my disk and use BlobToChar to built a C array code with the header. With this dump I can load the header in my code and parse it quickly.

First 64 bytes (Header):

1

2

3

4

5

6

$ hexdump -C -n64 /usr/bin/ls

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 03 00 3e 00 01 00 00 00 20 5b 00 00 00 00 00 00 |..>..... [......|

00000020 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 b0 23 02 00 00 00 00 00 |@........#......|

00000030 00 00 00 00 40 00 38 00 0b 00 40 00 1b 00 1a 00 |....@.8...@.....|

00000040

Dumping on disk:

1

2

3

4

$ dd if=/usr/bin/ls of=lselfheader bs=1 count=64 [130]

64+0 records in

64+0 records out

64 bytes copied, 0.000510657 s, 125 kB/s

Load in code in C arrays:

1

2

3

$ BlobToChar --blobname lselfheader

unsigned char buff[] = {0x7f,0x45,0x4c,0x46,0x2,0x1,0x1,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x3,0x0,0x3e,0x0,0x1,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x20,0x5b,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x40,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0xb0,0x23,0x2,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x40,0x0,0x38,0x0,0xb,0x0,0x40,0x0,0x1b,0x0,0x1a,0x0,};

unsigned int buff_size = 64;

The parse code can be written as:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

#include <elf.h>

#include <stdio.h>

unsigned char buff[] = {0x7f,0x45,0x4c,0x46,0x2,0x1,0x1,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x3,0x0,0x3e,0x0,0x1,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x20,0x5b,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x40,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0xb0,0x23,0x2,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x40,0x0,0x38,0x0,0xb,0x0,0x40,0x0,0x1b,0x0,0x1a,0x0,};

unsigned int buff_size = 64;

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

Elf64_Ehdr* elfHeader = (Elf64_Ehdr*) buff;

printf("e_ident: %s\n", elfHeader->e_ident);

}

As structs are just aligned bytes in memory, we can use the struct Elf64_Ehdr to parse these raw bytes, with this we can access the elf header internal struct. In the above example I printed the e_indent, which is an array with some basic information on the file itself, stored in the first 16 bytes of the buf variable. The very first 4 bytes: 0x7f,0x45,0x4c,0x46 contains the ‘ELF’ string starting from the second position.

1

2

~ >>> ./parseheader

Magic: ELF

Knowing that, we can now parse the whole file by reading the file itself and use the ELF structs to extract the executable data itself.

Example: Patching sections names

Let’s make a cool example, let’s change the .text section name to another thing. This section holds all the executable code in the file.

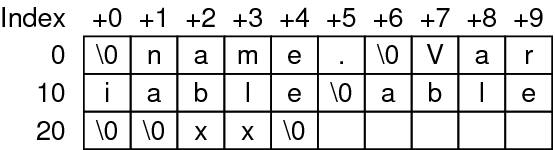

In order to make that possible, we need to have access to the string table struct, which holds an array of strings with the 0x00 byte as delimiter.

As the string table is just one portion of data in the file, it’s defined as a normal section and the struct in x64 elf is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

typedef struct {

uint32_t sh_name;

uint32_t sh_type;

uint64_t sh_flags;

Elf64_Addr sh_addr;

Elf64_Off sh_offset;

uint64_t sh_size;

uint32_t sh_link;

uint32_t sh_info;

uint64_t sh_addralign;

uint64_t sh_entsize;

} Elf64_Shdr;

With this struct in our hands, we just need to get the index of the section name (sh_name) and change it to something else. Notice that if we want to make the name greater or less then the real one, we will have to resize this array and change all the sections and address information to maintain the file integrity, in order to make this simple as possible I will just change the .text name to .etxt.

Loading the entire file in memory

Before we continue, let’s make some real code for this task and for that we need to load the file data in our memory, just like a loader would.

To map files in memory in Linux, we will use the function mmap that will create a in memory mapping to a given file descriptor.

Function definition:

1

2

3

4

#include <sys/mman.h>

void *mmap(void *addr, size_t len, int prot, int flags,

int fildes, off_t off);

Using this idea, take a look in the following code to load our ELF file and dump the header, we will use this piece of code for the example part:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

#include <elf.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s <elf_path>\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

const char* elf_path = argv[1];

int file_fd = open(elf_path, O_RDWR); // Open in read and write

if (!file_fd) return 1;

struct stat st; // Get file size using stat function

stat(elf_path, &st);

unsigned file_size = st.st_size;

// Map the current file descritor in any address in ours memory maps with size <file_size>

void* addr = mmap(NULL, file_size, O_RDWR, MAP_SHARED, file_fd, 0);

if (!addr) return 1;

// Now we can work the new memory space using the raw address

Elf64_Ehdr* elf_header = (Elf64_Ehdr*) addr;

puts("elf->e_indent: ");

for (int i = 0; i < EI_NIDENT; ++i) {

printf("\t0x%x(%c)\n", elf_header->e_ident[i], elf_header->e_ident[i]);

}

// Unmap the values

munmap(addr,file_size);

// Close the file descriptor

close(file_fd);

return 0;

}

If you compile the code above, you will get something like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

elf->e_indent:

0x7f()

0x45(E)

0x4c(L)

0x46(F)

0x2()

...

Finding the section string table

Ok, now let’s start the real job to get the section named .text. In order to accomplish that we need the first entry in the section array structure and get the total bytes used by this array, all this information can be found in the following field of the elf header:

e_shnum- Holds the number of sections that our ELF file hase_shentsize- Holds the total raw size of each sectione_shoff- Holds the offset of the first entry in the array

Knowing all that, we can calculate where the section array starts by getting the address of the mapped file + the e_shoff and then create a for loop where each “jump” is the index * e_shentsize, that way we can jump in each element of the array, after reaching the .text section we can get where in the string table it’s name is defined.

1

2

3

4

5

6

Elf64_Ehdr* elf_header = (Elf64_Ehdr*) addr;

uint16_t num_sections = elf_header->e_shnum;

uint16_t section_size = elf_header->e_shentsize;

Elf64_Off section_entry_offset = elf_header->e_shoff;

printf("%d Sections, with %d bytes each and starting at address 0x%x\n", num_sections, section_size, (uint64_t) addr + section_entry_offset);

25 Sections, with 64 bytes each and starting at address 0x82702f68

Your numbers might differ based in the file that are you using and the mapped address that is used to calculate the entry of the array.

Now, we need to find the string table that will be used as an array, lucky for us, the index string table in the section array is easily found in the ELF header, in the field e_shstrndx, to find the address using this index we just need to get the address of the first entry in the array and multiple the index with the size of each section.

pseudo-code:

1

2

3

string_table_address = (index * section_size) + first_entry_address

or

string_table_address = section_size + section

Or even better, we can just get the first section address and just add the section_size, if you are familiar in how an array really works in memory, this will be easy to understand.

C code:

1

Elf64_Shdr* string_table_section = (Elf64_Shdr*) ( (uint64_t) section + ((uint64_t) section_size * elf_header->e_shstrndx));

Finding the .text string index

Now with the section header loaded, we can find the offset where the section data is stored, as this is only the header and the real content is in another place in the file, this data location is found in the field sh_offset in the section header, so in order to find the array we just need to get the mapped file address + section->sh_offset.

After find the raw data in the file we just need to work how it’s is specified in the ELF specs, this is a normal C-String array with the \00 as delimiter.

C code to find the first entry in string table:

1

section_name = (char*) (( (uint64_t) string_table_section->sh_offset + addr) + 1);

This will access the string array and get the first element, in order to pick the sections name we need access the field sh_name in the section header that holds the name index of this section in the string array, using that we can iterate in each section of the file and get each name easily, check the code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Elf64_Shdr* section = (Elf64_Shdr*) ((uint64_t) addr + section_entry_offset);

Elf64_Shdr* string_table_section = (Elf64_Shdr*) ( (uint64_t) section + ((uint64_t) section_size * elf_header->e_shstrndx));

char* section_name;

for (int i = 0; i < num_sections; ++i) {

section = (Elf64_Shdr*) ((uint64_t) section + section_size);

section_name = (char*) (( (uint64_t) string_table_section->sh_offset + addr) + section->sh_name);

}

Changing the .text name

Now, it’s pretty simple, we can modify the name directly and as this file is mapped in memory in read-write mode our changes will be flushed directly in the disk file, take a look:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

for (int i = 0; i < num_sections; ++i) {

section = (Elf64_Shdr*) ((uint64_t) section + section_size);

section_name = (char*) (( (uint64_t) string_table_section->sh_offset + addr) + section->sh_name);

if (!strcmp(section_name, ".text")) {

strcpy(section_name, ".txet");

}

}

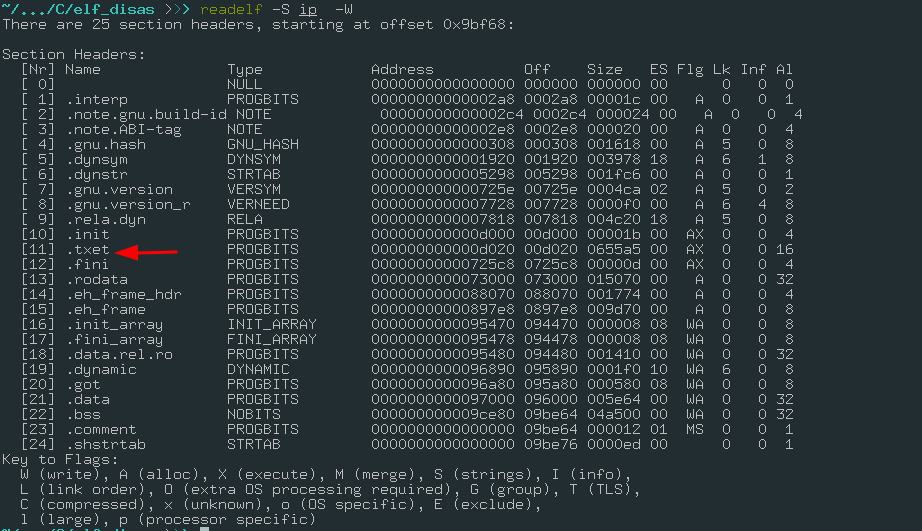

Now take a look using readelf command to get all sections name:

The program still works because the new name is following all the elf specs, and it’s a valid one.

Enter felf

Now let’s start the real reason of this article, let’s talk about felf.

Why felf

A couple months, I wanted to build a simple program that extract section hashs of a bunch of elf files, I also wanted to write that in C++ because it’s a languange that I enjoy, and I want to write everything from scratch without any helper library.

My project didn’t worked the way I wanted and I just abandoned it, but I developed new cool library in C++ to work with elf files, that’s the story.

The name Felf came from the nasm command parameters, if you will want to build a elf file from a nasm file, you pass the paremeter -f with value elf, almost everyone use that two together so the whole command become nasm -felf…

Installing

Felf is written in C++ using cmake, so in order to install you will need any modern cpp compiler (g++, llvm…) and of course, cmake

Automatic installation

1

2

git clone https://github.com/buzzer-re/felf.git

cd felf && ./install.sh

The installation script will build for release and install/strip the shared libraries

First time using

Let’s start by the simplest operation possible, load and print the elf magic number, just like we did before from scratch, in felf this is very simple to perform.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#include <felf/ELF.h>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

ELF elf("/usr/bin/ip", MAP_RO);

if (elf.valid()) {

std::cout << "Elf loaded, parsing e_indent value\n";

unsigned char* e_indent = elf.elfHeader->e_ident;

for (int i = 0; i < EI_NIDENT; ++i) {

std::printf("e_indent[%d] = 0x%x(%c)\n", i, e_indent[i], e_indent[i]);

}

}

}

Compile:

g++ -o header_dump header_dump.cpp -lfelf++

Let’s breakdown this call:

- ELF constructor needs the path for the file and the open mode

- You also should check if the file is a valid elf file, this is done by a magic number test

- Almost all internal structures are now mapped inside the ELF object

When opening a file, you must tell felf how to map this file in memory, as this is using mmap from behind the scenes:

-

MAP_RO: Map the file in Read only mode in memory

-

MAP_RW: Map the file in Read-Write mode in memory, if you want to patch the file somehow, this will reflect directly in the file.

-

MAP_EX: Map the file in Read-Execute mode in memory

Please refer to the structures section in the README file, this will show all the structures that are currently supported/mapped.

Cool usages

Symbol and Section dump

With this library in mind, we can now do a lot of useful operations quickly using the internal structures, the first one I want to show it’s a simple symbol and section dump using the Symbol table and the Section table structure.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

#include <felf/ELF.h>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

if (argc != 2) {

std::fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s <path_to_elf>\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

ELF elf(argv[1], MAP_RO);

if (elf.valid()) {

std::printf("Dumping symbol table with %d symbols\n", elf.symbolTable.length);

for (auto it = elf.symbolTable.symbolDataMapped.begin(); it != elf.symbolTable.symbolDataMapped.end(); ++it) {

std::printf("Symbol name: %s\n", it->first.c_str());

}

std::printf("\n\nDumping section table with %d symbols\n", elf.elfSection.length);

for (auto it = elf.elfSection.sectionsMapped.begin(); it != elf.elfSection.sectionsMapped.end(); ++it) {

std::printf("Section name: %s at ", it->first.c_str());

std::printf("0x%x\n", it->second->sh_offset);

}

'

}

}

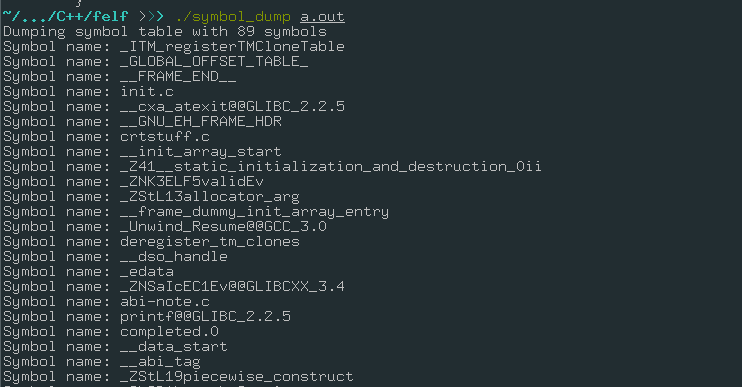

The above code takes a input elf file, map into memory in read-only mode and parse all the elf structures, the internal variable symbolTable it’s a good example of why I created this library, you can access the unordered_map, that is a C++ implementation of a hashtable without order, and that holds all the symbols names as key and the SymbolData structure as value, this means that if you can quick lookup any of symbol in the file you can just use the find.

Output:

Symbol dumping

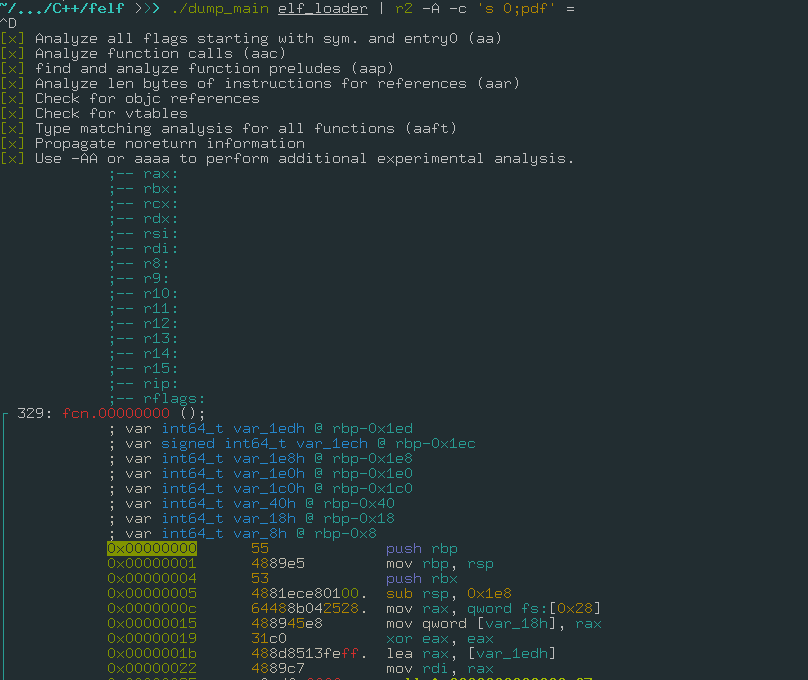

Using the same idea above, in the next example I will dump the raw data of the main, if the binary isn’t stripped, and pipe that out to radare2.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

auto symbolIter = elf.symbolTable.symbolDataMapped.find("main");

if (symbolIter != elf.symbolTable.symbolDataMapped.end()) {

// Found

// Loop in SymbolData structure raw data

for (unsigned i = 0; i < symbolIter->second->size; ++i) {

std::printf("%c", symbolIter->second->data[i]);

}

}

Ignoring all the code that load and check the file, the code above it’s pretty straight forward, make a quick lookup at the symbolData map, and extract the raw data of this symbol to the stdout, with that I will pipe that out to radare2 framework and disassemble all (print disassembly all aka pdf).

Very cool, right?

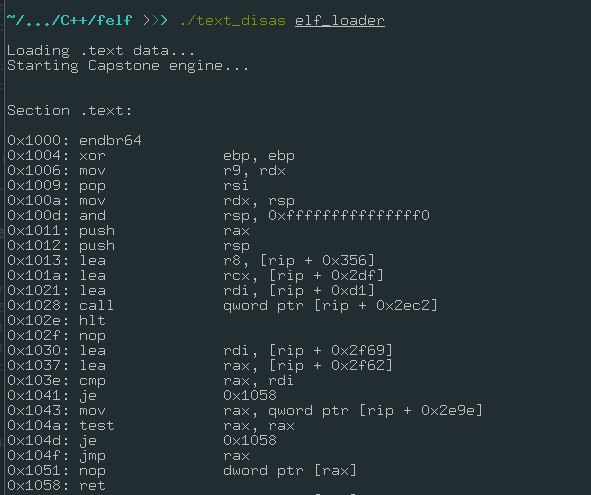

Elf disassembly

Now that we fully understand the power of this simple library, let’s build something cool from scratch, a ELF disassembler, for this we will need to write our asm parser or use a already created library for that, I will use the Capstone engine to perform that for us, so go grab that before continue (if you are trying the examples above), and take a look at a simple example using this engine.

In order to disassemble something, we must get the valid instructions that contains the opcodes, opcode are just a byte that has a meaning in the CPU, and the readable value of this opcode is called mnemonic, so the opcode 0x55 has the mnemonic push and the operators xbp where x differ based in the arch of the CPU, in x64 it’s rbp and x86 ebp, in order words, if one executable section of our memory contains any raw byte and the Instruction pointer are pointing to that area, our CPU will read this instructions and execute that.

For the sake of simplicity, I will disassembly the .text section of a elf file, I will use the sectionTable map to extract the raw data of this section and use the capstone engine to disassembly that.

The section data

To get the section data you just need to use the internal variable elfSection and extract the length and their raw data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

std::cout << "Loading .text data...\n";

auto sectionIter = elf.elfSection.sectionData.find(".text");

if (sectionIter != elf.elfSection.sectionData.end()) {

unsigned char* sectionData = sectionIter->second->data;

std::cout << "Starting Capstone engine...\n";

std::cout << "\n\nSection .text:\n\n";

capstone_disas(sectionData, sectionIter->second->size);

}

And the capstone_disas function is written as:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

void capstone_disas(unsigned char* data, unsigned size)

{

csh handle;

cs_insn* insn;

size_t codeCount;

if (cs_open(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64, &handle) != CS_ERR_OK) {

std::cerr << "Error when starting capstone!\n";

return;

}

codeCount = cs_disasm(handle, data, size, 0x1000, 0, &insn);

if (codeCount > 0) {

unsigned j;

for (j = 0; j < codeCount; ++j) {

std:: printf("0x%"PRIx64":\t%s\t\t%s\n", insn[j].address, insn[j].mnemonic, insn[j].op_str);

}

cs_free(insn, codeCount);

}

}

This function, starts the capstone engine in x86 architecture and in x64 mode, then we just send the whole data that we want to disassemble and the cs_insn struct pointer, that holds information like the mnemonic value and operators values.

Compile:

g++ -o text_disas text_disas.cpp -lfelf++ -lcapstone

Run:

Ready to build your own reverse engineering tools ?

Conclusion

You see that this tiny and little x64 elf parser can do, and it’s has a very simple code to parse everything in C++ structures, I hope that this article helped you to understand more about the ELF format and executable formats in general.

This project has a lot potential to grow up, and I have a lot ideas like: Python and Golang bindings, Code refactoring and more support for different architectures.

Thanks for reading all this, and if this article has any mistake, fell free to open a issue in the felf project and I will fix.

Revision by: @jvslg